You’ve probably heard that birds are descendants from dinosaurs, and new evidence of bird feathers that were preserved in 99-million-year-old amber from Myanmar are helping prove this point. Not only do these feathers provide crucial insights into the evolutionary history of modern birds, but they are shedding some more light on other potential factors contributing to the extinction of their ancestors.

These remarkable feathers give a unique view into the past, showing the significance of molting and how this resulted in some early extinctions.

In addition, this discovery represents the first definitive fossil evidence of juvenile molting in birds, which were reportedly the only type of dinosaurs to have survived the supposed asteroid strike that wiped out the rest of the non-avian dinosaur population some 66 million years before.

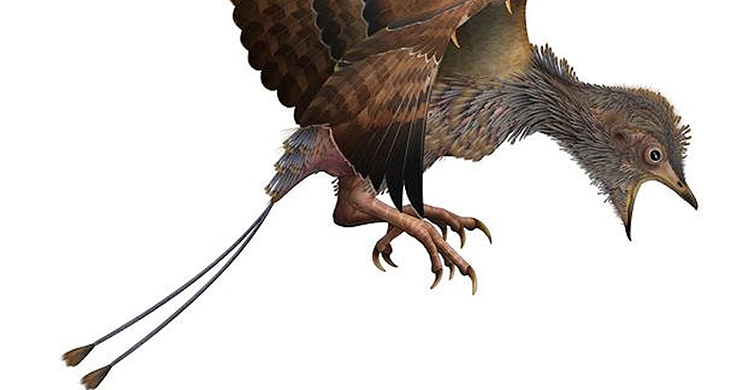

The bird in the spotlight, named Enantiornithine, had to keep warm despite rapid shedding, explains scientists. And losing its feathers was one major factor to the birds’ ultimate demise.

Professor Jingmai O’Connor of The Field Museum Chicago, who published the research in the journals Cretaceous Research and Communications Biology, said, “Enantiornithines were the most diverse group of birds in the Cretaceous, but they went extinct along with all the other non-avian dinosaurs.”

“When the asteroid hit, global temperatures would have plummeted and resources would have become scarce, so not only would these birds have even higher energy demands to stay warm, but they didn’t have the resources to meet them,” he added.

The prevalent consensus among scientists is that birds are a subgroup of theropod dinosaurs that emerged during the Mesozoic Era, spanning from 252 to 66 million years ago.

Feathers, which are primarily composed of a protein called keratin (similar to human fingernails and hair), undergo molting because they cannot be repaired.

Today, two main types of birds exist: altricial and precocial. Altricial birds hatch without feathers and rely on their parents for direct body heat transmission, while precocial birds are born with feathers and are relatively self-sufficient.

“Molting is fundamentally such an important process to birds, because feathers are involved in so many different functions,” said Prof. O’Connor.

“We want to know, how did this process evolve? How did it differ across groups of birds? And how has that shaped bird evolution, shaped the survivability of all these different clades?”

Molting is an energy-intensive progress. Moreover, losing tons of feathers at the same time leads to many challenges, but the main one for birds is maintaining their body temperature. As mentioned earlier, while precocial birds tend to molt gradually, which ensures a continuous supply of feathers, altricial birds on the other hand, get food and warmth from their parents, and undergo a “simultaneous molt” when their feathers shed all at once.

Prof O’Connor explained, “This specimen shows a totally bizarre combination of precocial and altricial characteristics. All the body feathers are basically at the exact same stage in development, so this means that all the feathers started growing simultaneously, or near simultaneously.”

In modern adult birds, molting typically occurs once a year in a sequential fashion with a few feathers replaced at a time over several weeks, allowing them to continue flying during the molting process. Simultaneous molting is more common in aquatic birds like ducks.

To gain further insights into this ancient avian molting pattern, researchers examined over 600 modern bird specimens at the Field Museum.

First study author, Dr. Yosef Kiat, said, “Among the sequentially molting birds, we found dozens of specimens in an active molt, but among the simultaneous molters, we found hardly any.”

Although these are modern birds and not actual fossils, they are still considered to be useful proxies.

“In paleontology, we have to get creative, since we don’t have complete data sets,” said Professor O’Connor.

“Here, we used statistical analysis of a random sample to infer what the absence of something is actually telling us,” he adds.

The findings indicate that prehistoric birds, particularly those from groups that did not survive the mass extinction event, likely molted differently from most modern birds, possibly molting less frequently or simultaneously rather than following the yearly cycle observed today.

Professor O’Conner also said, “All the differences that you can find between crown birds and stem birds, essentially, become hypotheses about why one group survived and the rest didn’t. I don’t think there is any one particular reason why the crown birds, the group that includes modern birds, survived. I think it is a combination of characteristics.”

“But I think it is becoming clear that molt may have been a significant factor in which dinosaurs were able to survive,” he added.

What are your thoughts? Please comment below and share this news!

True Activist / Report a typo